This article uses Fretspace to explore the Major scale and its modes. The Major Pentatonic scale can be regarded as a simplified version of the full Major scale, which has seven notes and is the foundation of western musical harmony. Alternatively, the Major scale can be regarded as an extension of the Major Pentatonic scale.

Chords, scales, and the cycle of fifths

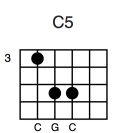

There is an interesting way to relate the Major Pentatonic scale to the full Major scale, and it is based on the cycle of fifths. Natural notes (as opposed to sine waves) are accompanied by a series of harmonic overtones. The first overtone after the fundamental note is an octave above the fundamental note. An octave is the simplest and least dissonant interval that you can play. The second overtone is a fifth. After an octave, the simplest chord that you can play is a “power chord”, which contains a root and a fifth. This is often notated as a “5” chord. Here is a C5 power chord:

Power chords are neutral chords. They don’t contain a third, so they can be used in place of major or minor chords.

We can go on adding fifths to create more complex forms of harmony. Adding a fifth to C5 (C G) gives us C G D, which is a suspended chord (Csus2 or Gsus):

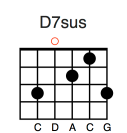

Suspended chords, like power chords, are neutral chords that are neither major nor minor. Adding a fifth above D gives us C G D A, which contains a minor third interval (A to C). A chord with these notes could be a suspended chord (D7sus, Gsus/9, or C6sus2) or a minor eleventh chord without a fifth degree (Am11):

Adding a fifth above A gives us C G D A E, which contains a major third (C to E) as well as a minor third. Arranging these notes as a chord, we have a chord that is either C6/9 or Am11 (with fifth degree):

Alternatively, by arranging these notes as a scale, we have a C Major Pentatonic scale, or an A Minor Pentatonic scale:

What this tells us is that by taking five notes that are a fifth apart, we have arrived at a basic scale that contains many of the fundamental elements of harmony, including fifths and thirds.

So what happens if we keep adding notes that are a fifth apart? Let’s add a note that is a fifth below C (F) and a note that is a fifth above E (B), which gives us F C G D A E B. Rearranging these notes as a scale gives us the scale of C Major: C D E F G A B. The Major scale can therefore be regarded as equivalent to the Major Pentatonic scale, with the addition of two extra notes from the cycle of fifths.

These added notes are interesting. The dominant chord in the key of C is G7, and the notes that we added, which aren’t in the Major Pentatonic scale, are B (the third degree of G7) and F (the minor seventh degree). Together these notes form a tritone (six semitones) which creates a degree of tension that is normally resolved by moving to a C chord. The third degree (B) normally moves up by a semitone to become the root of C, and the minor seventh degree normally moves down by a semitone to become the third degree of C (E). In contrast to the Major Pentatonic scale, the Major scale contains semitone intervals that can be used to move smoothly from dominant chords to root chords.

Major scale shapes

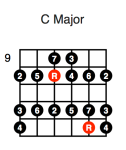

Since there are seven notes in the major scale, it is possible to create seven box shapes in which each shape begins with a separate note. But it is simpler to take the five Major Pentatonic shapes that we have already know and extend them by adding a fourth (F) and a major seventh (B) to each shape:

This gives us five shapes that correspond to the five shapes of the Major Pentatonic scale. As you would expect, these five shapes can also be used to play a minor scale, which is sometimes referred to as the Natural Minor scale to distinguish it from other minor scales.

The Natural Minor scale is related to the Major scale in exactly the same way that the Minor Pentatonic scale is related to the Major Pentatonic scale: it contains the same notes as the Major scale, but its root is a minor third (three semitones) below the root of the related Major scale. These scales can also be used in a similar way to the Major and Minor Pentatonic scales: the Major scale can be used to solo over tunes that are in a corresponding major key, and the Natural Minor scale can be used to solo over tunes that are in a corresponding minor key—sometimes.

Here is one example of a situation where this approach is not going to work. Am D (played repeatedly) is a common chord vamp, and you can play an A Minor Pentatonic over both chords, but it will sound terrible if you play an A Natural Minor scale over this progression. This is because A Natural Minor contains a minor sixth (F natural) which clashes badly with the major third (F#) of the D chord. You don’t have this problem with the A Minor Pentatonic scale, because it doesn’t contain a sixth note.

Major scale modes

There is a scale that works well over the Am D vamp, and it is a minor scale—but it is not the Natural Minor scale. The scale that we want to use with this vamp is known as the Dorian scale, and like the Natural Minor scale it is a mode of the Major scale. The Dorian scale sounds good with Am D because it contains a major sixth: F# in this case. Here is the first-position shape of the A Dorian scale compared with the first-position shape of the A Natural Minor scale:

This brings us to the topic of Major scale modes. There are seven modes, starting on each note of the Major scale: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian. The Ionian mode starts from the root of the Major scale, so it is simply another name for the Major scale played from its root: the fact that the name begins with I can be used as a mnemonic that this is the I (Roman 1) form of the scale. The Aeolian mode starts from the sixth degree of the Major scale, so it is another name for the Natural Minor scale. The fact that the Aeolian mode of C Major starts from A is a helpful mnemonic. The Dorian mode starts from the second degree of the Major scale, and the fact that the Dorian mode of C Major starts from D is another helpful mnemonic.

Here are the seven modes of the C Major scale, in first-position boxes:

As you can see, the Phrygian and Lydian modes have the same first-position shapes, as do the Ionian and Locrian modes.

We noted earlier that there are minor progressions which require a Dorian scale rather than an Aeolian (Natural Minor) scale. There are also major progressions which require a different scale than the Ionian (Natural Major) scale. Take the following progression: D C G D. This looks like a D major progression, because it starts and ends on D, and you could play a D Major Pentatonic over it, but if you try playing a D Major (Ionian) scale you will find that it sounds bad. The problem in this case is that the D Major (Ionian) scale contains a major seventh (C#) which clashes with the second chord (C). The scale that we want to use with this progression is actually the Mixolydian scale, which differs from the Ionian scale in that it contains a minor seventh (C in this case) rather than a major seventh (C#). Here is the first-position D Mixolydian shape, compared with the first-position D Ionian shape:

A good way to understand modes is to relate them to chords. There are three major modes: Ionian, Lydian, and Mixolydian. These relate to the three major chords (I, IV, and V) of any major key. In the key of C, the C Ionian scale corresponds to a C major chord, F Lydian corresponds to an F major chord, and G Mixolydian corresponds to a G major chord. The V chord in any key is also known as the Dominant chord, and it is often played as a dominant seventh (G7 in the key of C), so you can see that the Mixolydian scale with its minor seventh matches the dominant seventh chord, which also has a minor seventh: G7 and G Mixolydian both contain F natural (a minor seventh) rather than F# (a major seventh). By contrast, the Ionian and Lydian scales contain major sevenths, so they can be played over major seventh chords (Cmaj7 and Fmaj7 in the key of C).

In addition to the three major modes, there are three minor modes: Dorian, Phrygian, and Aeolian. These relate to the three minor chords (ii, iii, and vi) of any major key. In the key of C, the D Dorian scale corresponds to a Dm chord, E Phrygian corresponds to an Em chord, and A Aeolian corresponds to an Am chord. Finally, the Locrian mode is a half-diminished mode that corresponds to the half-diminished (vii) chord of any major key.

Chord/scale soloing

One way to approach soloing, as we’ve seen, is to use the same scale over all the chords that are in a tune or progression, and this works well with simple tunes and progressions, but it breaks down in less simple cases. Take the following progression: C C7 F C. Here we are in the key of C, so we can play a C Major scale over most of these chords—but it is going to sound bad if we play a C Major scale over C7 because B natural (in the scale) will clash with Bb (in the chord). Similarly, with the following progression: C D7 G7 C. Here a C Major scale will sound fine with most of the chords, but it will clash with D7 (F natural versus F#). The C Major Pentatonic scale doesn’t have these problems because it omits the fourth and seventh degrees (F and B).

The way to deal with this is to use the Mixolydian mode in both these cases. This is the mode that corresponds to the dominant seventh chord, so it works well with most dominant seventh chords—so long as they are not followed by a minor chord (this takes us into the area of minor harmony, which we will look at in a later article).

This brings us to an alternative method of soloing, which is to match scales with chords rather than keys. Both methods are perfectly valid, but chord/scale soloing is useful in cases where a progression moves outside the key signature, as in the two progressions we looked at above. Jazz musicians use chord/scale soloing as a way of navigating through complex progressions. Jazz progressions often tend to be complex variations of ii V I progressions, so a jazz musician might use Dorian as the default scale for minor chords, Mixolydian as the default scale for dominant chords, and Ionian or Lydian as the default scale for other major chords. The Lydian scale is often preferred in jazz, because the sharp fourth helps to avoid clashes with the major third of the associated chord—but you can use whichever scale sounds best to you. Sometimes an Ionian scale sounds good in cases where you might naturally use a Lydian scale. Take the following progression: G D C Am. Here we are in the key of G and C is the IV chord, so the natural scale to use is C Lydian (which contains F#) but in fact C Ionian (with F natural) also sounds good at this point. Ultimately, it is your ears that have to decide what sounds good and what doesn’t—but it helps if you know what your choices are to begin with!

The Locrian scale can be used with half-diminished (m7b5) chords.

Reference charts

Let’s add a Major chart to our collection of reference charts. Open the Guitar Scales document that you should already have—if you don’t, go back and create it, following steps in the Pentatonic Scales article.

Major chart

Select the Major Pentatonic chart in the Charts area on the left of the window and drag it to the bottom of the list while holding down the Option key. This will create a copy of the Major Pentatonic chart. Rename this copy to Major.

Major shapes

- Delete the Minor Pentatonic shapes and Sus6/9 shapes, so you are left with a line of five Major Pentatonic shapes.

- Change the first fret of the last box to be 4, using the First Fret field in the Inspector panel. (This allows room for a note to be added at the fourth fret.)

- Option-click in each of the boxes to add a seventh note (one fret before a root note) and a fourth note (one fret after a third note). This will convert them into Major shapes.

Dorian shapes

- Select the line of Major shapes (including the line break at the end), copy them (⌘C), and paste them back (⌘V), so you have a second line of Major shapes.

- Select each shape in turn and change its name to D Dorian using the Name drop-down list in the Inspector panel (click on the down-arrow and choose D Dorian from the list).

- Drag the first shape to the end of the line, so that the first-position shape (which starts with the colored root note) is first.

Phrygian shapes

- Select the line of Dorian shapes (including the line break at the end), copy them (⌘C), and paste them back (⌘V), so you have a second line of Dorian shapes.

- Select each shape in turn and change its name to E Phrygian using the Name drop-down list in the Inspector panel.

- Drag the first shape to the end of the line, so that the first-position shape (which starts with the colored root note) is first.

Lydian shapes

- Select the line of Phrygian shapes (including the line break at the end), copy them and paste them back, so you have a second line of Phrygian shapes.

- Select each shape in turn and change its name to F Lydian using the Name drop-down list in the Inspector panel.

- There’s no need to drag the first shape to the end of the line: a first-position Lydian shape is the same as a first-position Phrygian shape.

Mixolydian shapes

- Select the line of Lydian shapes (including the line break at the end), copy them and paste them back, so you have a second line of Lydian shapes.

- Select each shape in turn and change its name to G Mixolydian using the Name drop-down list in the Inspector panel.

- Drag the first shape to the end of the line, so that the first-position shape (which starts with the colored root note) is first.

Aeolian shapes

- Select the line of Mixolydian shapes (including the line break at the end), copy them and paste them back, so you have a second line of Mixolydian shapes.

- Select each shape in turn and change its name to A Aeolian using the Name drop-down list in the Inspector panel.

- Drag the first shape to the end of the line, so that the first-position shape (which starts with the colored root note) is first.

Locrian shapes

- Select the line of Aeolian shapes (including the line break at the end), copy them and paste them back, so you have a second line of Aeolian shapes.

- Select each shape in turn and change its name to B Locrian using the Name drop-down list in the Inspector panel.

- Drag the first shape to the end of the line, so that the first-position shape (which starts with the colored root note) is first.